la Biennale di Venezia

CentrePasquArt

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

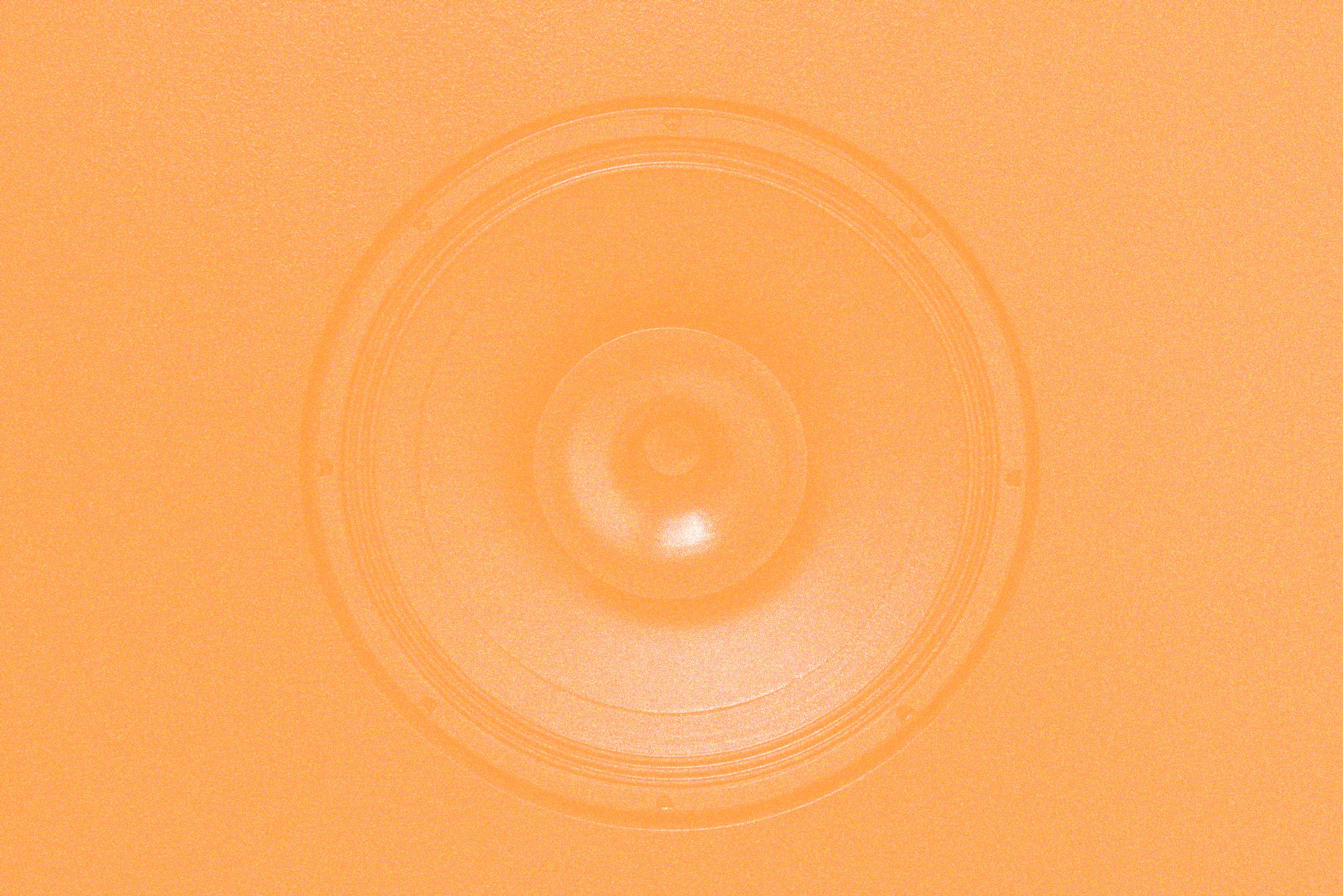

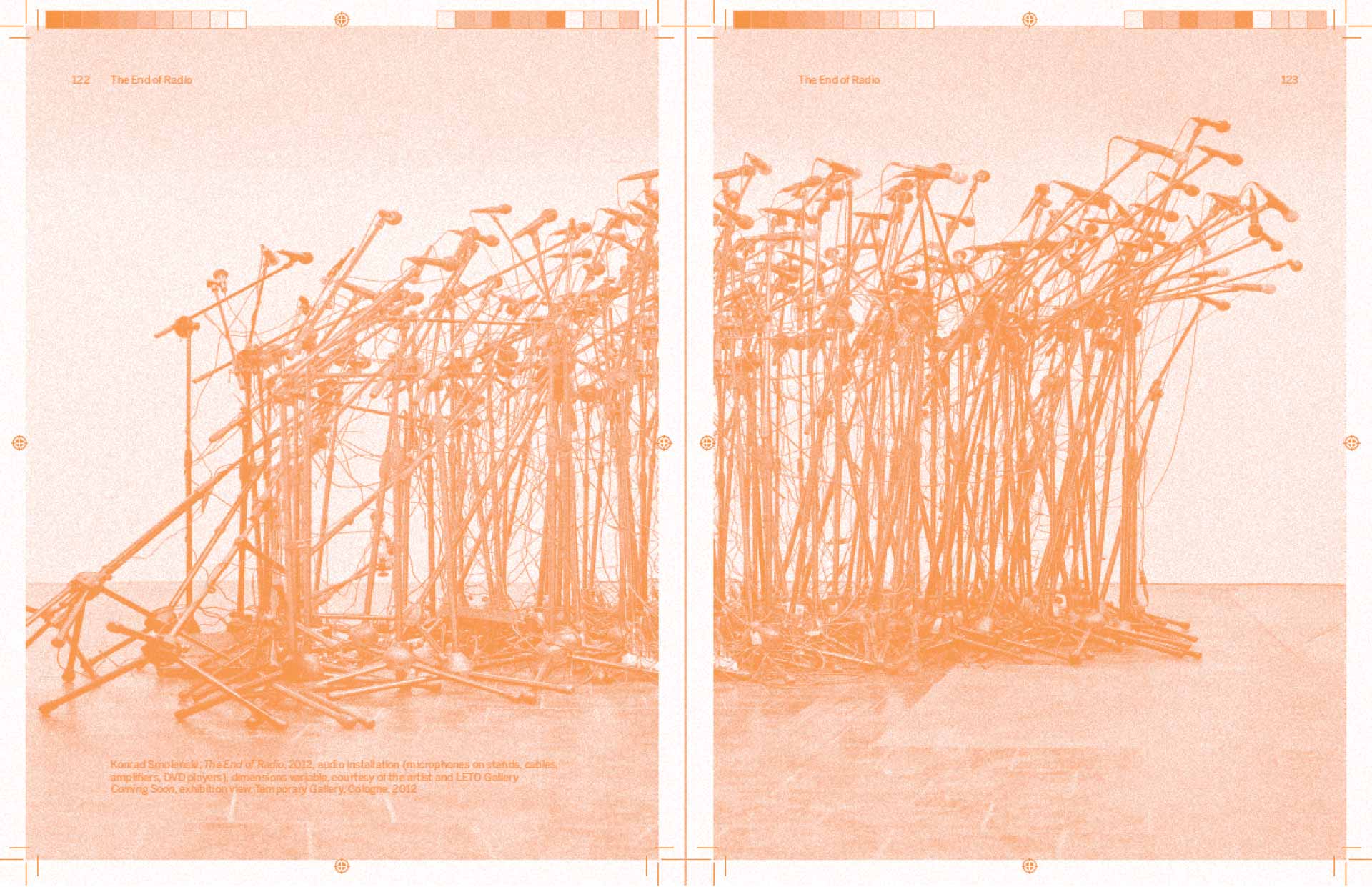

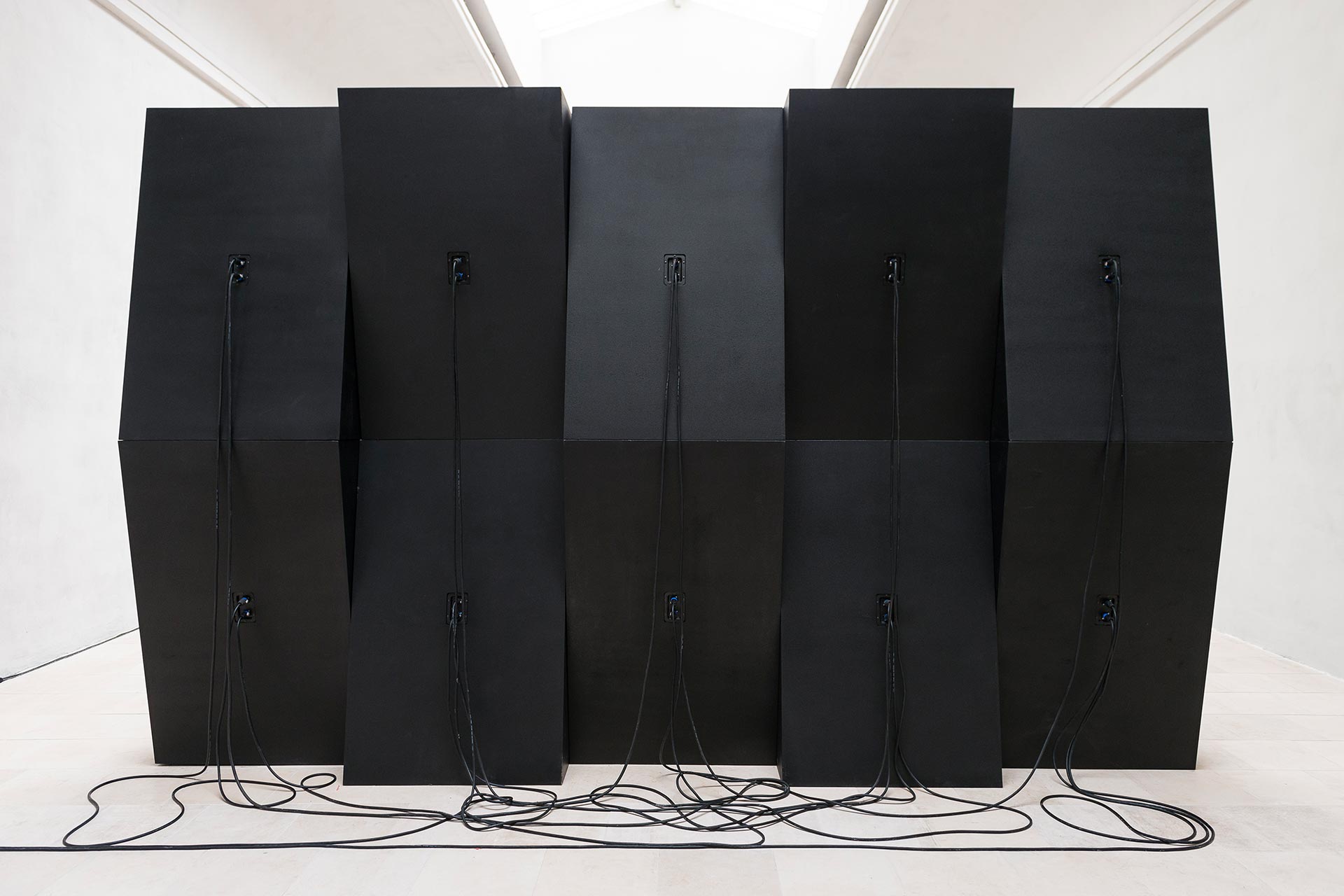

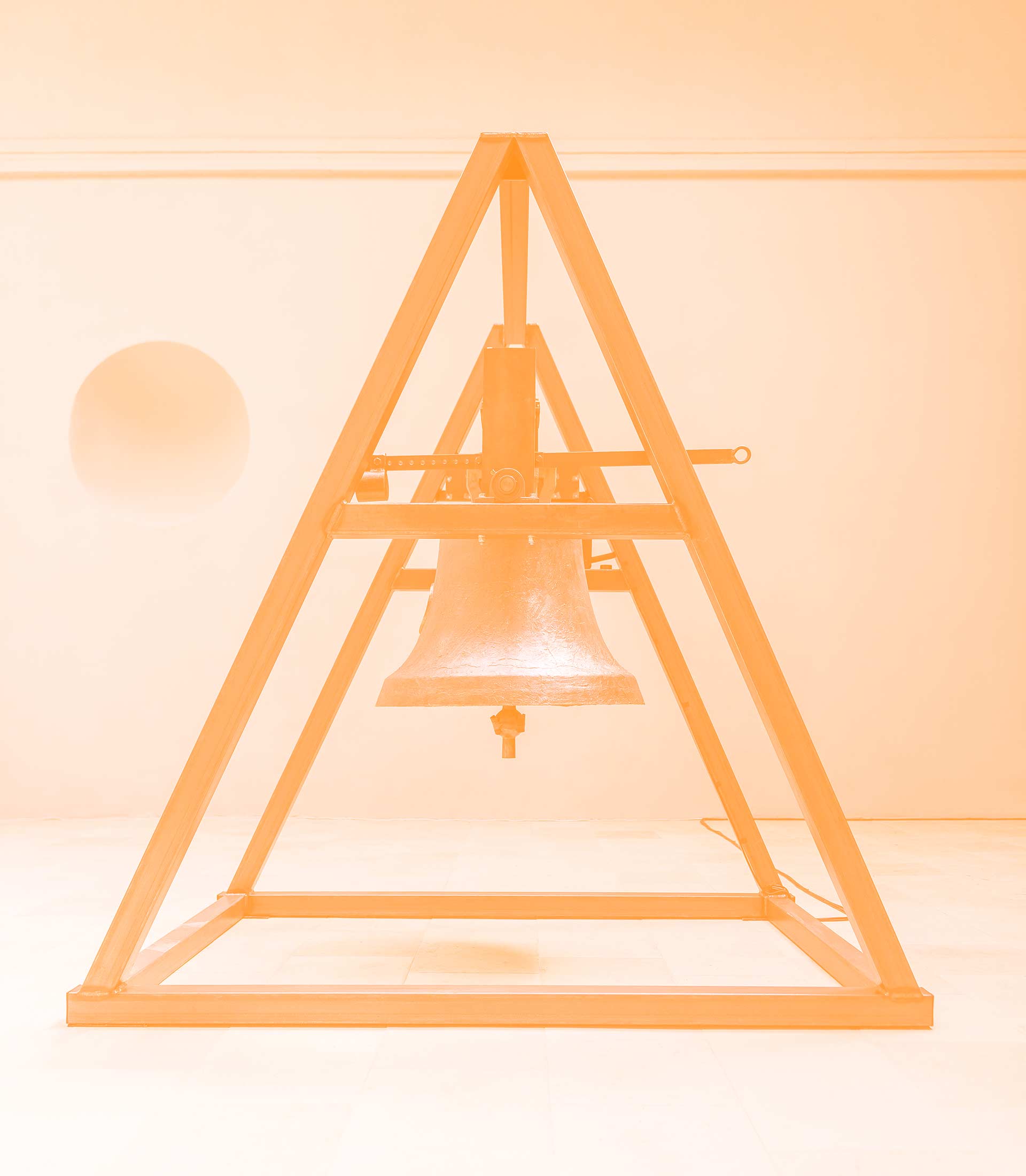

Konrad Smoleński, an active participant in both the independent music scene and the visual art scene, blends punk-rock aesthetics with minimalist precision. Everything Was Forever, Until it Was No More is a sculptural instrument that reproduces, at regular intervals, a music piece written for bronze bells, wide range loudspeakers, and other resonating objects. The composition is based on a contrast between the symbolically rich sound of the bells and the abstract resounding noise. By using a delay effect, Smoleński offers an insight into a world where history has come to a standstill, thereby approaching the radical propositions of contemporary physics with its perception of the passage of time as an illusion. The exhibition is accompanied by a publication featuring texts by Craig Dworkin, Alexandra Hui, Andrey Smirnov, as well as Daniel Muzyczuk and Agnieszka Pindera, who, in their previous projects undertaken together or individually, have already commented on the problems pertaining to the field of the history of science and sound. Supplementing this interdisciplinary book are interviews with a physicist Julian Barbour, a philosopher Simon Critchley, a legend of electro acoustic music Eugeniusz Rudnik, and the curator Thibaut de Ruyter.

10 October – 16 November 2013

Zachęta – National Gallery of Art

Konrad SmoleńskiEverything Was Forever, Until It Was No More - Time Test

Curators: Daniel Muzyczuk & Agnieszka Pindera

Collaboration on the part of Zachęta: Joanna Waśko

Audio equipment: Tomasz Marek Stage Service

Organizer of the exhibition: Zachęta — National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

www.zacheta.art.pl

6 July – 17 August 2014

CentrePasquArt/Kunsthaus Centre d'Art — Biel/Bienne

Konrad SmoleńskiEverything Was Forever, Until It Was No More - Time Test

Exhibition curators: Daniel Muzyczuk and Agnieszka Pindera with Felicity Lunn

Assistant: Damian Jurt

Engineer: Paolo Merico

Audio equipment: Tomasz Marek Stage Service

Organizer of the exhibition: CentrePasquArt

www.pasquat.ch

Exhibition co-organized by Zachęta — National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

www.zacheta.art.pl

1 June – 24 November 2013

The Polish Pavilion at the 55th International Art Exhibition — la Biennale di Venezia Venice

Konrad SmoleńskiEverything Was Forever, Until It Was No More

Polish Pavilion Commissioner: Hanna Wróblewska

Exhibition Curators: Daniel Muzyczuk and Agnieszka Pindera

Assistant Commissioner: Joanna Waśko

Organizer of the exhibition: Zachęta — National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

www.zacheta.art.pl

Bells’ casting: Kruszewski Brothers Bell Foundry

Bells’ construction assembly and engine: PRAIS Company

Audio equipment: Tomasz Marek Stage Service

Architecture: Agnieszka Staszek and Anna Galek

Photo documentation: Bartosz Górka

Graphic design: Dagny and Daniel Szwed – Moonmadness

Web development: Rafał Jara - Fabric

Polish participation in the 55th International Art Exhibition in Venice was made possible through the financial support of Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland.

The exhibition is organized in cooperation with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

Shipping Sponsor: FF Fracht

Acknowledgements:

Steve Albini, Maciej Formanowicz, Magdalena Formanowicz, Maria Florczuk, Ania Galek, Bartosz Górka, David Grubbs, Mats Gustafsson, Alexandra Hui, Rachel Kamins, Leszek Knaflewski, Marta Kołakowska, Katarzyna Krakowiak, Michał Kupicz, Michał Libera, Jarosław Lubiak, Małgorzata Ludwisiak, Ewa Łączyńska-Widz, Paweł Polit, Vincent Ramos, Robert Rumas, Agnieszka Staszek, Jarosław Suchan, Dagny i Daniel Szwed, Justyna Wesołowska, Adam Witkowski, Alexei Yurchak.